'I Thought He Was a Messenger': Making Stevie Wonder's 'Talking Book'

Producer Robert Margouleff talks about his memories in the studio recording the classic album that turned 40 this week—and the frustrations that came later.

By the start of the 1970s, Little Stevie Wonder had grown up to become one of the most popular acts in music. After releasing 12 albums for Motown, he let his original contract expire on his 21st birthday in 1971. As a result, he recorded two independent albums and used them as a negotiating tool when Motown was trying to get him to sign a new contract. Wonder succeeded in gaining more creative control over his music, and his "classic period" of artistic genius began with the release of Music of My Mind (1972).

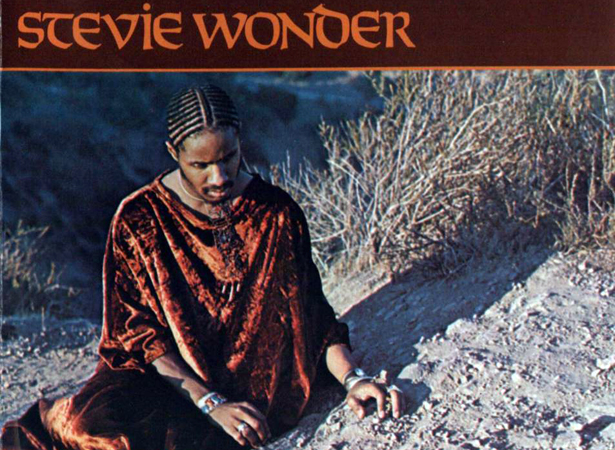

Later on in the same year, Wonder would catapult himself into another realm of superstardom with the legendary album , Talking Book. It showcased Wonder's brilliance and the talent of two producing architects, Robert Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil. Their revolutionary work with synthesizers helped in shaping Wonder's groundbreaking sounds. On the occasion of Talking Book's 40th anniversary this week, I spoke with Margouleff about recording one of the greatest albums ever.

MORE ON MUSIC

Coming into the making of Talking Book, what kind of transition were you trying to make with Stevie from Music of My Mind and some of his earlier work?

We took it one day at a time. Sometimes when you make music and stuff, you don't listen to the sound of your own wheels. We didn't have a conscious thing saying that we were going to do something different with Stevie. We did what we thought served the songs and we incorporated some of things we've done from our past experiences. It was interesting with Talking Book. Music of My Mind was released on March 3, 1972. Talking Book came out on the 28th of October during the same year. This is how busy Malcolm and I were with Steve. We had organization and a structure.

In terms of the direction for the sound of the album, what was the process like working with your partner (Malcolm Cecil) and Stevie Wonder in the studio?

Originally, it was just the three of us in the studio. We did what came naturally to us. We would bounce ideas off of each other. There were no real boundaries. We all had our job descriptions and we did what we could. We were very open with each other. Stevie would ask how something would sound and if I didn't like it I would say, "It sounds like a doorbell." It was just a natural time. There wasn't a lot of preconceived energy. It was very impulsive.

Were the bulk of the songs completed in the studio?

Yes. Steve would come in with a line or something sometimes because he had a clavinet at his house. Recording equipment at that time wasn't really portable. Most of the time Steve would come in around 6:30 or 7 o'clock at night and we would work until 5 in the morning. That would generally be the pattern. Malcolm and I would come in around 4:30 and Stevie would come in and we would have things already prepared. We would keep a long list of projects and songs we were working on. We would keep them in a little loose-leaf binder and we would keep track of where we were with specific songs.

We really never cut songs for an album. We started recording material and at the end of five years we stopped recording. It was more like cutting material for a library than an album. When it came time to put an album together, we would sit on the floor in his office in New York and we would say, "Oh, let's do this one." Then we would say, "No. Steve. This one needs background vocals and more orchestration."

We did 160 songs together. It was an ongoing process of picking songs. Some of those songs have never seen the light of day that I know of. Steve was the final judge. He is the artist. There is no finer singer, performer, and songwriter than Stevie Wonder. He might not have given us the recognition that we thought we deserved, but that in no way diminishes his talent.

What was it like working with a young genius during his prime?

It was a joy in the beginning. I would say Music of My Mind, Talking Book, and Innervisions were great, then it got to be laborious for a variety of reasons. One, we weren't getting paid properly. Two, the studio started filling up with people who were to just there to fan the air and suddenly become official people. It became less and less pleasant to work with him.

The music was always good. We tried to preserve the music, but the vibes got to be really heavy because we weren't being taking care of correctly. The more famous he got, the less recognition we got. It really became a trial. At that point, we decided it was time to move on.

But during the making of Talking Book, it was a joy to work with him. It was at the height of everything. There was total loyalty and total belief. There's a time that you think it was going to go on for forever and that you can never make any mistakes. Every record we touched turned to gold, whether it was for Stevie or for other artists. All we had to do was walk into the studio and do what we did best.

We needed Stevie because Stevie really reflected the times. He had an important message. I felt like his music making superseded the entertainment business. His music reflected the cry for civil rights, the urban black experience, and about who he was. I felt like his music was very political and I came from a political background. He didn't just write love songs, but he related to the world's reality at that time. I thought he was a messenger. What he had to say was really important, and it's proven to be that way. Here we are 40 years later, and we can remember the songs. We might have had our business differences, but we didn't have any differences in our philosophy and the music.

After the fourth album, we started repeating ourselves and, I have to say, not in a low way, but I think Steve has concentrated the next 40 years of his album-making experience of trying to repeat the experiences of those albums we made together including the sound. We used to turn out a record every 18 months. Why did that stop? He surrounded himself with people he was more comfortable with. Malcolm and I were kind of prickly and white [laughing]. He felt a little out of his element, maybe. I don't know honestly.

I don't feel badly towards Steve. I wouldn't mind a $100,000 check for me and Malcolm. I'm 71 years old. I don't have that much mileage left. I mean—that would be nice in our retirement and golden years for him to remember what we did for him, but I think that's highly unlikely. I don't see any reason to not state what really happened at this point. I thought we were treated badly in the end. As the albums went on, our credits got smaller and smaller. It was an amazing experience. We know what we did. Steve knows what we did. I don't know what happened, but we really lost touch with each other. Towards the end, Malcolm wouldn't even come in the studio, which was sad.

It was like this, there were three points of light and they all came together, and there was this bright flash for five years. During those five years, it was a magical time. It was beautiful. We made some really great records and we felt we were going in the same direction. I regret that it ended the way it did. The music making during Talking Book was at our best. The best vibe, the best emotional time and the most complete expression of what we were doing. We weren't repeating ourselves in any way. We were there for all the right reasons. There were no extraneous players in the game.

Stevie, me, and Malcolm had a beautiful routine. I would keep a record log of all the songs and where we were periodically to see what we needed to do. When he would come into the studio, there would be something up on the board for him to work on. The studio was always ready. We used to put all the instruments that he would play for a session in a big circle in the studio. They were always all up. The drums were always tuned up and ready to go. The piano, clavinet, the Rhodes, the synthesizers and all the things we had were pretty much in a big circle so Steve could overdub and walk from one instrument to the other. If he needed, we would tune up the drums a little bit or adjust something. We would experiment with the microphones to make sure it was the right microphone for the song. We generally operated autonomously. Most of the time recording studios had staff engineers. Well, with Stevie we were employees of Stevie's and not employees of the studio or the record company. We really hit our stride in two places.

Electric Lady Studios was an interesting experience. Some of the material for Talking Book was recorded there. The studio was built by my dear friend, John Storyk. He built the studio originally for Jimi Hendrix. It was built by an artist for his own work, which was one of the first in the world. Most studios were very big, clumsy, and industrial, and had staff engineers, and were maintained and operated by the record companies. There was a certain sprinkling of independent studios in New York such as Bell, Media, etc. There were about six of them there. We were working at Media for the start of the album and we couldn't stay there. Media was basically was built for commercial recordings like Ford Motor Company. I was the resident synthesist there and Malcolm was the night maintenance man though he was playing jazz bass with a bunch of major players at that time like Jim Hall. We had the studio at night. Steve wanted to be working all the time and we would have to keep breaking down our setups because during the day it was for commercials.

So—we found Electric Lady. Jimi was in the process of going to England and within that eight-week time span he was gone. And here's a studio built completely for an artist. It was the shoe that we put our foot in. Steve kind of replaced Jimi in a strange kind of way. The room was so conducive to creativity. It had mood lighting, which I know Steve didn't respond to it, but it made everyone else kind of mellow around the place. It was the kind of place that he could move around in and go to the bathroom without having someone take him to the bathroom. With him being blind, he learned the place and the pattern of the studio so he could move around freely. It gave him a tremendous sense of freedom. We worked hard there, and then we started making little journeys to the West.

Berry [Gordy] and Ewart [Abner] decided to move Motown from Detroit to Los Angeles. Steve still felt very close to those guys although his contract was in the air at that time. He finally decided to be his own person in every way, and we were the tools of that in many ways. We gave him his independence in the studio. We worked for him and not for Motown. We didn't get checks from Motown. We came west and we all stayed at the Hallmark Motor Hotel on Sunset Blvd. He had a room, I had a room and Malcolm had a room. We had our little Arp synthesizers all interconnected and they would be playing each other from room to room. You would hear all the electronica out in the swimming pool area. It was like a courtyard motel. Then we started working at a place called Crystal Studios. And again we got crowded out because Crystal Studios was the home of Joni Mitchell. It was a beautiful place.

We worked there for awhile, and the guys from the Record Plant Studios came to me and Malcolm and we went to Gary Kellgren's old house up on Camino Palmero St. We struck up a deal with them. They said, "If you want to buy studio time for Steve, we'll build the studio for you, if you guarantee to book studio time for him." So we were buying studio time for Stevie by the year. And we built a beautiful room. John Storyk came out from New York and we brought TONTO out there.

When we were negotiating for the studio, I'll never forget what happened. Gary Kellgren bought down a bottle of Courvoisier and we touched our glasses to make a toast and then there was an earthquake. It started off like that. At Record Plant, it was like jet propulsion from there. The studio itself contributed to the whole thing of it. It was just an amazing time. We couldn't do anything wrong. It's all I can tell you. We just made music, music, music. We were really able to exercise our liberties. We had our own tape library there. Across the hall we had a Jacuzzi so if we wanted to take a little break we could jump in the Jacuzzi. People were crazy. I used to smoke pot. I got high until I couldn't see my own feet. It was good times. I will never be sorry that I did it. I don't have any regrets. If Stevie had shown a little more generosity and a little more sense of equality towards us outside of the studio, we would've stuck around a lot longer.

Can you discuss the making of some songs from Talking Book?

"You're the Sunshine of My Life" was such an up tune. People would call it the "Stevie Wonder song." He ended up being on top of the world. We started with the Fender Rhodes part and then the Moog part. But the earlier records were more overdub parts with Stevie playing everything. The more we got into the records, the more the band started playing on the records. It wasn't a hard record to make because everything just fell together.

The thing about Stevie and us and about our recording technique in general is you will know the records are very dry. There isn't a lot of echo and reverb on it. The reason is because we always felt that echo and reverb commentate distance—something being farther away, and therefore, you could add more instruments the further away it was you could make the orchestra bigger and bigger. What we wanted to do was to have a more intimate experience. For example, if you listen to the drum tracks, you can see all of the hi-hats come up on the left. The reason for that is that the only person who can hear the drum kit in surround-sound stereo is the drummer. The further away you get from the drum kit, the more mono it becomes, so if you listen to our records with Stevie the hi-hats are on the left because we recorded the drums from the point of view of the drummer and not of the listener.

We also did all of our monitoring in quad. We had a beautiful API console in studio B at the Record Plant, which also enabled me to bring some of the instruments into the control room so Steve could sit in the middle and have the clavinet in the back and the Rhodes in the front and the background vocals coming from the back of the room. By spreading all of the instruments out, we were able to really equalize correctly and to get stuff to sound really good. By the time we got to the mixing, there was very little EQing done. We would monitor in quad for the recordings, which was also inspirational to Stevie. Then, we would do what we called in the early days 'Armstrong automation.' Me, Malcolm, and Stevie would be at the console rehearsing our moves and we would mix the thing all in one pass. We had all of our moves marked on the faders and so on and so forth.

This is how all of our records were made together. He was just a great songwriter. He wasn't the Justin Bieber of his time. He wasn't some kind of chemical person. Justin Bieber is corporate music. Stevie's music came right out of his head.

"You and I (We Can Conquer The World)" was done with Stevie and his girlfriend sitting on the piano bench next to him. He played the piano first.

"Superstition" was originally written for Jeff Beck. He decided it was too good to give away so he kept it for himself. He started out playing the drums. The first track down was the drums. The whole song was in his head. Stevie is a genius. He is one of the greatest living songwriters of our generation, no question. He may be the greatest ever. God might have taken his sight, but he put his thumb on his forehead because Stevie is full of music.

"Blame it on the Sun" was Stevie's song about heartbreak. We recorded it in the same classical way. I don't remember how we pulled it all together. The lyrics were very heavy. He was saying you have to blame yourself and not others for loves lost. He had heavy things going on. Again, it was small instruments, not lots of layers. If you listen to any of those records, you will see there are only a small group of instruments. The Moog synthesizer was a monophonic instrument. You could play one sound or event at one time. We could do two or three because TONTO was a multiple of monophonic synthesizers with a common tuning bust so we could tune them all and transpose them all simultaneously. But they were each individual instrument so Steve could only play one or two lines at a time. We played with chamber-size music with a quartet basically. We were very, very spare.

"Maybe Your Baby" had a great bass line. Again, the songs were done in all the same manner. We would lay down the keyboards and what not.

What are your feelings 40 years later on making one of greatest albums in the history of music?

For me, Talking Book is the greatest record I made in my life, period. It never got better than that. It was the most heartfelt, most emotional, and most inventive. We were all equals. There were two other people besides Stevie who genuinely cared about the music, and I think it showed. Malcolm and I were right by his side for the three or four best albums of his career. We made some of the greatest music ever.